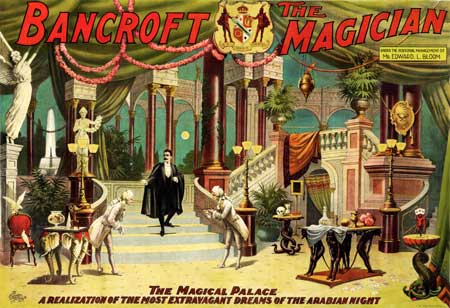

Introduction The sixth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Based on its own merits, I found it to be a really unique and interesting book about art history (philosophy?) and the way we see the world around us. I loved its unique format of interspersing images with commentary, where the two blended together seamlessly and actually commented on each other. But in juxtaposition with the previous two books of the Book Club, it was even more compelling and spurred even more ideas (and questions). Ways of Seeing built directly upon Philip Fisher’s Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences (1) and its themes of wonder through sight and the creation of knowledge. It also reminded me a lot of George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying (2) and its themes of commercializing art and the struggle between market demands and artistic integrity. It also spurred many new questions and ideas around the effect of the camera on how we see art (and magic!). Seeing, Wonder, Knowledge, and Manipulation The first essay in Ways of Seeing introduced the connection between how we see and what we know, and this idea builds directly on the major themes from Fisher’s Wonder. John Berger writes, “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” This means that before creating any sort of knowledge or communication, one must first see and perceive. This is very similar to Fisher’s writing about wonder. Fisher writes that “Wonder and learning are tied by suddenness... the moment of first seeing... the visual presence of the whole state or object.” He defines “Intuition” as “the visual moment of seeing.” Not only do the two authors agree that seeing comes before knowledge and words, but they both emphasize that it is through the emotions caused by seeing that we are spurred to think, explore, and create words and make sense of the world. Thus, Fisher writes, “Philosophy begins in wonder.” Both authors also emphasize the relationship between what we see and what we know. Fisher explains, “From wonder to thought: the passage sets off a chain of experiences built on ever repeated small scale repetitions of the experience of wonder…. Wonder makes us learn and retain in our memory things that until then we were ignorant of.” Conversely, John Berger points out that “the way we see things is affected by what we know or believe.” And this sight can be influenced by someone else, like a magician or marketer. Berger also explains that “We can only see what we look at.” And one’s look can be manipulated. Not only do magicians have control over what their audience sees and doesn’t see, but the way they see things (“what [they] know or believe”) can be affected by many choices the magician makes. Thus, the core of creating the right experience for our audience is to carefully craft the “sight” the viewer sees and the context (words, stories, beliefs) around that sight. Words (“philosophy”) are the end result of the process of scientific discovery spurred by wonder. And words can be manipulated just as effectively as what others see. However, the sight (the physical) is still the more powerful influence, no matter what you say or teach someone. Berger writes, “Knowledge of the earth turning doesn't fit the sight of the sun setting.” Even if someone tells you that the sun isn’t really moving down vertically into the ocean, nothing can shake that feeling you get when looking at a sunset over the beach. The "sight" can influenced by the words you use to describe it, but most of what determines your feeling is still the intuitive (the visual). Art, Magic, and Market Demands The essays in the middle of Ways of Seeing taught some important historical lessons about the role of paintings in the marketplace, it was interesting for me to learn how the objects depicted inside paintings actually played an important psychological role for their owners. Berger comments, “Paintings show sights of what a person may possess…. Art [can be seen] as display of property.” To support this, he provides numerous paintings as evidence showing the depictions of many gold objects in luxurious palace rooms filled with even more paintings and art. He explains how the “master” painters of the Renaissance were actually the exceptions to the rule: most painters just focused on creating paintings that gave their owners images of wealth that they could hang in their homes to make themselves feel rich and proud. Another interpretation he offers is that these opulent paintings served as a way for people to experience a feeling of dreaming and striving; the paintings showed them what wealth could be like and gave them something to hope for. In the same way that a painting can “show sights of what a person may possess,” a magic experience can show sights of what one might be able to do or create. Often by seeing the impossible, we are inspired to work harder and to find new meaning and hope in life. In fact, through the ages, many scientists have similarly been inspired to invent and analyze, energized by the sight of something that most around them considered impossible. I personally find this the most compelling reason to perform magic: creating hope and inspiration to explore what might be possible. Throughout all his discussion of art and the role of the professional artist, Berger makes several references to the “demands and commissions of the open art market.” This is in direct comparison with the principles inherent in artistic integrity and the artists’ personal choices of subjects and themes. This directly ties into Orwell’s depictions of Gordon Comstock’s depressing struggle between the demands of the market (his job) and his artistic freedom and pursuits. It’s also a vital question that magicians face as well, deciding between opportunities to earn money and staying true to their own artistic principles. The Effect of the Camera on Art and Magic One of Berger’s essays has a lot of profound observations about the effect of the camera. He writes, “The invention of the camera changed the way men saw.” Whereas an artist could depict multiple perspectives in a painting or various abstract representations of reality, a camera captures a specific point of view and feeling (within which there can be many details and levels of expression). Berger explains that “the camera started showing things differently from the imagination and the infinity of perspective of painting.” While a painting is defined completely by the artist’s imagination and can include multiple perspectives, the camera allows the photographer to choose a viewpoint and a subject, but the rest is dictated by reality (and perhaps less the imagination). Drawing parallels to magic, it seems like magic is more like painting in that it is a selective recreation of something in reality by the magician (artist) rather than a perfectly realistic capture of reality; in fact, the magic is defined by the ways in which it achieves things that aren’t possible in reality and which exist in the audience’s imagination: "Magic is in the mind of the spectator -- not in your fingers" (3). Berger also explains how the camera changes the image it captures: “When the camera reproduces the painting, it destroys the uniqueness of its image. As a result, its meaning changes. Or more exactly its meaning multiplies and fragments into many meanings.” The camera allows for reproduction and mass-dissemination of an image, which makes it available to all but less unique. There is certainly something valuable gained, but Berger reminds us that there is also a cost to this. In magic, there is a world of difference between live performance versus recording. Everyone hates the notion of “camera tricks,” and the magical feeling is significantly weaker when you don’t experience it in person. The camera can be seen as a metaphor for technology in general, and similar lessons and cautions can be drawn that apply to magic. Some technology can be enabling, producing new and more powerful experiences, and spreading good knowledge to more people. But other technology can de-humanize the experience and promote shortcuts due to lowered attention span. We should always consider the costs and benefits of new approaches and keep in mind that what has been working effectively for the longest time may have a very good reason for being the way it is already (4). Conclusion The sixth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was really thought-provoking and fun to read. It directly built upon lessons I learned from the previous two books, and it sparked many new ideas and questions about what it means to see, what an image represents, and how to approach the world (and magic) in a more thoughtful, artistic way. It also makes me wonder what other unique formats for academic books could be interesting, such as interspersing other types of media and perhaps even interactive elements to convey a book’s points. And thus, inspired by the format of Ways of Seeing, I conclude with an image as well. References

1. Philip Fisher. Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences. 2003. 2. George Orwell. Keep the Aspidistra Flying. 1936. 3. John Hamman. The Secrets of Brother John Hamman. 1989. 4. Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. 2012.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Subscribe |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed