Introduction The seventh selection of Half Half Man’s book club was Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. It was a haunting and chilling book for me to read. I didn’t particularly like the subject matter or the plot development; I kept getting angry at the characters (but maybe the author’s intention was indeed to provoke strong emotion). What I did enjoy were the themes of beauty and art that the book brought up, as both relate directly to magic. And I thoroughly appreciated the actual beauty and art present at the meta-level of the book’s writing itself. The role of beauty in the book’s content Beauty seemed to me to be the central character of the book (not Dorian). It became Dorian’s mission in life, for which he traded his moral character and soul and towards which he sought any and every experience. Chapter 2 presented the dichotomy between beauty and intellect, and while such a contrast was likely meant to evoke strong emotion and show how many of Lord Henry’s principles were meant to be contrarian for the sake of being contrarian, it still didn’t sit well with me. Chapter 4 took this idea even further: “The search for beauty is the real secret of life.” And by Chapter 10, it was clear how devoted to the sensual life Dorian had become, studying perfumes, jewels, and music, and using any evil and sin possible to fill his different senses with some (superficial?) amount of beauty. I think that both beauty and intellect are worthwhile values and pursuits, and one doesn’t have to harm the other. This book showed how pursuing beauty to an extreme can be damaging, and the same can likely be shown for pursuing intellect alone. But I think each can have their place and merit. I think that in some ways Lord Henry’s (and subsequently Dorian’s) devotion to beauty was admirable in the sense of artistic commitment, but I kept wondering how else Dorian could have pursued and felt beauty without necessarily involving evil. The role of art in the book’s content One of the most physical incarnations of beauty in the book that served to demonstrate its power was art, and this art took different forms: paintings, music, and theater. Thus, art played an important role in the actual content of the book and served to illustrate the intoxicating (toxic?) influence of beauty on the characters. In Chapter 1, Wilde wrote about “art as the reflection of the artist more than the content.” This made think a lot about magic, as a performance usually shows a lot more about the magician and his or her style and character than the art form. Many important plot elements came to life through the theater and Sibyll Vane’s acting. In Chapter 6, Dorian even said, “I love acting. It is so much more real than life.” This reminded me of the oft-quoted idea that “life imitates art.” The theater played a central role in the book, creating Dorian’s first innocent emotions of love and romance and also spoiling it (and him) in the very same place. The theater was the place where the characters changed into new people, and the events that they saw on stage literally changed them afterwards. Many people think that theater is just for entertainment and to escape boredom (which was Lord Henry’s worst imaginable emotion to feel), but Wilde shows how it can actually have a profound impact on people’s lives, inspiring them for good and for evil. The role of beauty and art in the book’s writing What I did enjoy throughout the book the most was the actual beauty and art present in the book’s writing itself. Wilde’s masterful prose was clearly meticulously crafted to make a statement about how the English language can be wielded beautifully to tell a most ugly story. His writing reminded me more of poetry than prose: it was intricate, ornate, and carefully crafted. As Denis Behr remarked, Lord Henry “apparently cannot utter a comment that does not sound like a profound aphorism.” It’s self-evident how hard Wilde worked to literally decorate every page with such aphorisms and witty comments, and in this way, he showed himself to be like an artist with the written word. For me, this is the most inspiring part of this book for magicians learning to better script their effects. Conclusion The seventh selection of Half Half Man’s book club was for me a depressing and foreboding tale. It showed the power that beauty and art can have, and it showed how one’s obsessions can lead one to very dark places. Magicians have the power to make fantasy and impossible beauty come to life, and this power should be wielded carefully and towards good end. And they can learn a lot from Wilde’s expert writing and prose -- attention to every detail and making every statement be filled with beauty and purpose.

0 Comments

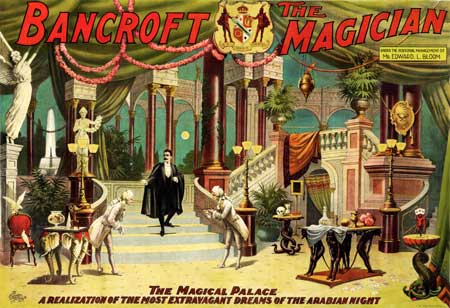

Introduction The sixth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Based on its own merits, I found it to be a really unique and interesting book about art history (philosophy?) and the way we see the world around us. I loved its unique format of interspersing images with commentary, where the two blended together seamlessly and actually commented on each other. But in juxtaposition with the previous two books of the Book Club, it was even more compelling and spurred even more ideas (and questions). Ways of Seeing built directly upon Philip Fisher’s Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences (1) and its themes of wonder through sight and the creation of knowledge. It also reminded me a lot of George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying (2) and its themes of commercializing art and the struggle between market demands and artistic integrity. It also spurred many new questions and ideas around the effect of the camera on how we see art (and magic!). Seeing, Wonder, Knowledge, and Manipulation The first essay in Ways of Seeing introduced the connection between how we see and what we know, and this idea builds directly on the major themes from Fisher’s Wonder. John Berger writes, “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” This means that before creating any sort of knowledge or communication, one must first see and perceive. This is very similar to Fisher’s writing about wonder. Fisher writes that “Wonder and learning are tied by suddenness... the moment of first seeing... the visual presence of the whole state or object.” He defines “Intuition” as “the visual moment of seeing.” Not only do the two authors agree that seeing comes before knowledge and words, but they both emphasize that it is through the emotions caused by seeing that we are spurred to think, explore, and create words and make sense of the world. Thus, Fisher writes, “Philosophy begins in wonder.” Both authors also emphasize the relationship between what we see and what we know. Fisher explains, “From wonder to thought: the passage sets off a chain of experiences built on ever repeated small scale repetitions of the experience of wonder…. Wonder makes us learn and retain in our memory things that until then we were ignorant of.” Conversely, John Berger points out that “the way we see things is affected by what we know or believe.” And this sight can be influenced by someone else, like a magician or marketer. Berger also explains that “We can only see what we look at.” And one’s look can be manipulated. Not only do magicians have control over what their audience sees and doesn’t see, but the way they see things (“what [they] know or believe”) can be affected by many choices the magician makes. Thus, the core of creating the right experience for our audience is to carefully craft the “sight” the viewer sees and the context (words, stories, beliefs) around that sight. Words (“philosophy”) are the end result of the process of scientific discovery spurred by wonder. And words can be manipulated just as effectively as what others see. However, the sight (the physical) is still the more powerful influence, no matter what you say or teach someone. Berger writes, “Knowledge of the earth turning doesn't fit the sight of the sun setting.” Even if someone tells you that the sun isn’t really moving down vertically into the ocean, nothing can shake that feeling you get when looking at a sunset over the beach. The "sight" can influenced by the words you use to describe it, but most of what determines your feeling is still the intuitive (the visual). Art, Magic, and Market Demands The essays in the middle of Ways of Seeing taught some important historical lessons about the role of paintings in the marketplace, it was interesting for me to learn how the objects depicted inside paintings actually played an important psychological role for their owners. Berger comments, “Paintings show sights of what a person may possess…. Art [can be seen] as display of property.” To support this, he provides numerous paintings as evidence showing the depictions of many gold objects in luxurious palace rooms filled with even more paintings and art. He explains how the “master” painters of the Renaissance were actually the exceptions to the rule: most painters just focused on creating paintings that gave their owners images of wealth that they could hang in their homes to make themselves feel rich and proud. Another interpretation he offers is that these opulent paintings served as a way for people to experience a feeling of dreaming and striving; the paintings showed them what wealth could be like and gave them something to hope for. In the same way that a painting can “show sights of what a person may possess,” a magic experience can show sights of what one might be able to do or create. Often by seeing the impossible, we are inspired to work harder and to find new meaning and hope in life. In fact, through the ages, many scientists have similarly been inspired to invent and analyze, energized by the sight of something that most around them considered impossible. I personally find this the most compelling reason to perform magic: creating hope and inspiration to explore what might be possible. Throughout all his discussion of art and the role of the professional artist, Berger makes several references to the “demands and commissions of the open art market.” This is in direct comparison with the principles inherent in artistic integrity and the artists’ personal choices of subjects and themes. This directly ties into Orwell’s depictions of Gordon Comstock’s depressing struggle between the demands of the market (his job) and his artistic freedom and pursuits. It’s also a vital question that magicians face as well, deciding between opportunities to earn money and staying true to their own artistic principles. The Effect of the Camera on Art and Magic One of Berger’s essays has a lot of profound observations about the effect of the camera. He writes, “The invention of the camera changed the way men saw.” Whereas an artist could depict multiple perspectives in a painting or various abstract representations of reality, a camera captures a specific point of view and feeling (within which there can be many details and levels of expression). Berger explains that “the camera started showing things differently from the imagination and the infinity of perspective of painting.” While a painting is defined completely by the artist’s imagination and can include multiple perspectives, the camera allows the photographer to choose a viewpoint and a subject, but the rest is dictated by reality (and perhaps less the imagination). Drawing parallels to magic, it seems like magic is more like painting in that it is a selective recreation of something in reality by the magician (artist) rather than a perfectly realistic capture of reality; in fact, the magic is defined by the ways in which it achieves things that aren’t possible in reality and which exist in the audience’s imagination: "Magic is in the mind of the spectator -- not in your fingers" (3). Berger also explains how the camera changes the image it captures: “When the camera reproduces the painting, it destroys the uniqueness of its image. As a result, its meaning changes. Or more exactly its meaning multiplies and fragments into many meanings.” The camera allows for reproduction and mass-dissemination of an image, which makes it available to all but less unique. There is certainly something valuable gained, but Berger reminds us that there is also a cost to this. In magic, there is a world of difference between live performance versus recording. Everyone hates the notion of “camera tricks,” and the magical feeling is significantly weaker when you don’t experience it in person. The camera can be seen as a metaphor for technology in general, and similar lessons and cautions can be drawn that apply to magic. Some technology can be enabling, producing new and more powerful experiences, and spreading good knowledge to more people. But other technology can de-humanize the experience and promote shortcuts due to lowered attention span. We should always consider the costs and benefits of new approaches and keep in mind that what has been working effectively for the longest time may have a very good reason for being the way it is already (4). Conclusion The sixth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was really thought-provoking and fun to read. It directly built upon lessons I learned from the previous two books, and it sparked many new ideas and questions about what it means to see, what an image represents, and how to approach the world (and magic) in a more thoughtful, artistic way. It also makes me wonder what other unique formats for academic books could be interesting, such as interspersing other types of media and perhaps even interactive elements to convey a book’s points. And thus, inspired by the format of Ways of Seeing, I conclude with an image as well. References

1. Philip Fisher. Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences. 2003. 2. George Orwell. Keep the Aspidistra Flying. 1936. 3. John Hamman. The Secrets of Brother John Hamman. 1989. 4. Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. 2012.  Introduction The fifth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying. I must admit it was quite a downer -- up until the last pages. I kept feeling angry and disappointed by the main character, Gordon Comstock, who is clearly talented but lets his talents go to waste because of absurd principles he stubbornly holds on to. In the end it is love (by accident) that forces him to wake up and find a way to make his life meaningful, and we can learn a lot from his sad story and apply it to our own artistic endeavors which often seem no less difficult than Gordon’s. Dedication to art and quality It’s immediately apparent to the reader that Gordon is talented and has a keen eye and ear for words and a deep love of books. He hates the idea of “jobs” and the only job that’s not completely offensive is working in a bookstore. For him, there is a clear delineation between books that are crap and books that are gold. When he comes home at night, penniless and hungry, his only consolation is rereading his favorite books. And when he sees advertisements or prose that’s poorly written, it incites in him a visceral anger. He is not just a “fan” of the English language used right; it is his life. And it is in the same way that he knows his body that he knows his art and written creations. Reading these things about Gordon reminded me of my favorite magicians and their dedication to their art and to quality. As I have tried to grow as a student myself, my appreciation has deepened for the immense amount of time and effort that professionals put into each element of their routines, each word, gesture, and move being an artistic and thoughtful choice. Real artists strive -- in fact, are ready to suffer -- for quality in the same way, no matter the art form. Principled or stubborn? Gordon’s love of poetry and art is his strength, but it is also the cause of his downfall. He turns his love of art into a hate for money (which is further reinforced by his poverty). In his mind, he can’t reconcile how life and society can be good while also being linked to money. For him, the most despicable idea is that of a “real job.” He struggles to figure out how to live by writing poetry and making art, and he fails to take advantage of opportunities that come his way even when he gets lucky breaks. As a result, he lets his skills and art go to waste out of pure stubbornness. This is a pretty sad and extreme counterexample to how an artist should be. There is certainly virtue in dedicating yourself to a principled existence and to giving 100% of your time and energy to a single cause, but the principles Gordon chose were counterproductive, and he never really dedicated himself in a professional way to his own art. Gordon’s is certainly a cautionary tale for any magician considering going full-time or struggling with a job in general. No matter what you apply yourself to -- magic or otherwise -- you always need to do your best, be productive, and focus on reality and principles that will lead to a rational, happy life. Professionalism and creativity This book certainly gets across the fact that creativity in art is hard work. But that’s not something that Gordon really knew how to do well. It’s clear how he struggled to write and create poetry, but it’s also clear how he lost the battle to procrastination, wasted time, and writer’s block. In the rare times he actually showed his work to others, he either squandered whatever success he found or let himself get completely hammered by rejection and self-doubt. He was not one to take feedback constructively. Gordon’s story is a warning to anyone who loves his or her art but struggles to do it professionally. Luckily, there is a better example and process, described eloquently by Steven Pressfield in his book, The War of Art (1). Pressfield does an excellent job effectively describing Gordon and his maladies in the concept which he coins “resistance.” It’s anything that gets in the way of sitting your butt down to write or create, to do the annoying, frustrating, and difficult work that needs to be done. Pressfield offers the concept of “turning pro” in the abstract sense as the solution: adopting the habits of a professional in your approach to art. This means having a morning routine, which many of the most successful artists do (2), showing up every day to your art like it’s your job, and forcing yourself through habit and explicit rules to get work done at all cost, even if it’s minimal or initially crappy. Conclusion The fifth selection of Half Half Man’s Book Club was a sad but important lesson in the struggle to create art in a practical real world. In the end, it is love that forces Gordon to use his talents and create art through his job. It is sad that he chose to give up on his poetry to do that, but as a professional, he will be able to create and produce words that impact people’s lives positively, and maybe one day he can return to the poetry that got him started. If he had approached his art like a professional from the beginning, it’s possible his life may have turned out quite differently. References 1. Steven Pressfield. The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. 2002. |

Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

Subscribe |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed